Tale of Two Brothers

| Tale of Two Brothers | |

|---|---|

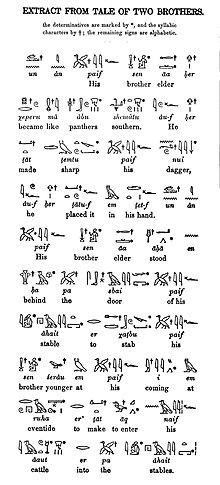

Sheet from the Tale of Two Brothers, Papyrus D'Orbiney | |

| Created | c. 1197 BC |

| Discovered | before 1858 |

| Present location | London, England, United Kingdom |

The "Tale of Two Brothers" is an ancient Egyptian story that dates from the reign of Seti II, who ruled from 1200 to 1194 BC during the 19th Dynasty of the New Kingdom.[1] The story is preserved on the Papyrus D'Orbiney,[2] which is currently held in the British Museum.

Synopsis[edit]

The story centers around two brothers: Anpu (Anubis), who is married, and the younger Bata. The brothers work together, farming land and raising cattle. One day, Anpu's wife attempts to seduce Bata. When he strongly rejects her advances, the wife tells her husband that his brother attempted to seduce her and beat her when she refused. In response to this, Anpu attempts to kill Bata, who flees and prays to Re-Harakhti to save him. The god creates a crocodile-infested lake between the two brothers, across which Bata is finally able to appeal to his brother and share his side of the events. To emphasize his sincerity, Bata severs his genitalia and throws them into the water, where a catfish eats them.

Bata states that he is going to the Valley of Cedars, where he will place his heart on the top of the blossom of a cedar tree, so that if it is cut down Anpu will be able to find it and allow Bata to become alive again. Bata tells Anpu that if he is ever given a jar of beer that froths, he should know to seek out his brother. After hearing of his brother's plan, Anpu returns home and kills his wife. Meanwhile, Bata is establishing a life in the Valley of the Cedar, building a new home for himself. Bata comes upon the Ennead, or the principal Egyptian deities, who take pity on him. Khnum, the god frequently depicted in Egyptian mythology as having fashioned humans on a potters' wheel, creates a wife for Bata. Because of her divine creation, Bata's wife is sought after by the pharaoh. When the pharaoh succeeds in bringing her to live with him, she tells him to cut down the tree in which Bata has put his heart. They do so, and Bata dies.

Anpu then receives a frothy jar of beer and sets off to the Valley of the Cedar. He searches for his brother's heart for three years and then another four years, finding it after searching for seven years. He follows Bata's instructions and puts the heart in a bowl of cold water. As predicted, Bata is resurrected.

Bata then takes the form of a bull and goes to see his wife and the pharaoh. His wife, aware of his presence as a bull, asks the pharaoh if she may eat its liver. The bull is then sacrificed, and two drops of Bata's blood fall, from which grow two Persea trees. Bata, now in the form of a tree, again addresses his wife, and she appeals to the pharaoh to cut down the Persea trees and use them to make furniture. As this is happening, a splinter ends up in the wife's mouth, impregnating her. She eventually gives birth to a son, whom the pharaoh ultimately makes crown prince. When the pharaoh dies, the crown prince (a resurrected Bata) becomes king, and he appoints his elder brother Anpu as crown prince. The story ends happily, with the brothers at peace with one another and in control of their country.

Context and themes[edit]

There are several themes present in the Tale of Two Brothers that are significant to ancient Egyptian culture. One of these is kingship. The second half of the tale deals largely with Egyptian ideas of kingship and the connection between divinity and the pharaoh. That Bata's wife ultimately ends up pregnant with him is a reference the duality of the role of women in pharaonic succession; the roles of wife and mother were often simultaneous. Also, the divine aspect of his wife's creation could be seen to serve as legitimacy for the kingship of Bata, especially since he was not actually the child of the pharaoh. Beyond this, Bata's closeness with the Ennead in the middle of the story also serves to legitimize his rule; the gods bestowed divine favor upon Bata in his time of need.

There are also several references to the separation of Egypt into two lands. Throughout ancient Egyptian history, even when the country is politically unified and stable, it is acknowledged that there are two areas: Lower Egypt, the area in the north including the Nile Delta, and Upper Egypt, the area to the south. In the beginning of the story, Bata is referred to as unique because there was "none like him in the entire land, for a god's virility was in him."[4] Additionally, whenever one of the brothers becomes angry, they are said to behave like an "Upper Egyptian panther," or, in another translation, like "a cheetah of the south."[5][6]

Interpretation and analysis[edit]

There are several issues to consider when analyzing ancient Egyptian literature in general, and the Tale of Two Brothers is no different. One difficulty of analyzing the literature of ancient Egypt is that "such scarcity of sources gives to the observation of any kind of historical development within Ancient Egyptian literature a highly hypothetical status and makes the reconstruction of any intertextual networks perhaps simply impossible."[7] Loprieno notes that the euhemeristic theory is often successfully employed in the analysis of ancient Egyptian literature; this the historiocentric method of analyzing literature as it pertained to political events.[8]

With relation to the Tale of Two Brothers, Susan Tower Hollis also advocates this approach, saying that the story might "contain reflexes of an actual historical situation."[9] Specifically, Hollis speculates that the story might have had its origins in the succession dispute following Merneptah's reign at the end of the 13th century BC. When Merneptah died, Seti II was undoubtedly the rightful heir to the throne, but he was challenged by Amenmesse, who ruled for at least a few years in Upper Egypt, although Seti II ultimately ruled for six full years.[10]

Folkloric parallels[edit]

According to folklorist Stith Thompson, the story is the predecessor to the Aarne–Thompson–Uther tale type ATU 318, "The Faithless Wife" or "Batamärchen".[11][12][13] Czech scholar Karel Horálek provided the "European redaction", that is, how the variants appear in European sources: the hero dies, resurrects as a horse; the horse is killed and from its blood a beautiful tree is born; the hero's unfaithful wife cuts down the tree; a woodchip remains and becomes a bird ("usually a drake").[14]

Parallels have also been argued between the resurrection cycle motif and tales that appear in later literary tradition, such as The Love for Three Oranges (or The Three Citrons), as well as mediaeval hagiographic accounts.[15]

Biblical parallels[edit]

The biblical account of Joseph and Potiphar's wife echo the fable of Bata and Anpu.[16] It is likely significant that this biblical story is stated to occur in Egypt.

Source of the text[edit]

- P. D'Orbiney (P. Brit. Mus. 10183); it is claimed that the papyrus was written towards the end of the 19th dynasty by the scribe Ennana.[17] It was acquired by the British Museum in 1857.[18]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Jacobus Van Dijk, "The Amarna Period and the Later New Kingdom," in "The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt" ed. Ian Shaw. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) p. 303

- ^ "Papyrus d'Orbiney (British Museum), the hieroglyphic transcription". Watchung, N.J., The Elsinore Press. 1900.

- ^ Budge, Wallis (1889). Egyptian Language. pp. 38–42.

- ^ William Kelly Simpson, "The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry" (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003) p. 81

- ^ Gaston Maspero, "Popular Stories in Ancient Egypt" (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002) p. 6

- ^ Maspero, Sir Gaston Camille Charles. Les contes populaires de l'Égypte ancienne. Paris: Guilmoto. 1900. pp. 1-20.

- ^ Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, "Does Egyptology need a 'theory of literature'?" in "Ancient Egyptian Literature" ed. Antonio Loprieno. (Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1996) p. 10

- ^ Antonio Lopreino, "Defining Egyptian Literature: Ancient Texts and Modern Theories" in "Ancient Egyptian Literature" ed. Antonio Lopreino. (Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1996) p. 40

- ^ Susan T. Hollis, "The Ancient Egyptian Tale of Two Brothers: The Oldest Fairy Tale in the World" (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996)

- ^ Jacobus Van Dijk, "The Amarna Period and the Later New Kingdom," in "The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt" ed. Ian Shaw. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) p. 303.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 275. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. p. 118.

- ^ Maspero, Gaston. Popular Stories of Ancient Egypt. Edited and with an introduction by Hasan El-Shamy. Oxford University Press/ABC-CLIO. 2002. p. xii and xxxiii. ISBN 0-19-517335-X.

- ^ Horálek, Karel. "The Balkan Variants of Anup and Bata: AT 315B". In: Dégh, Linda. Studies In East European Folk Narrative. American Folklore Society, 1978. pp. 235-236.

- ^ Hall, Thomas. “Andreas’s Blooming Blood”. In: The Wisdom of Exeter – Anglo-Saxon Studies in Honor of Patrick W. Connor. Edited by E. J. Christie. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020. pp. 197-220. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501513060-009

- ^ Walter C. Kaiser, Jr.; Paul D Wegner (20 November 2017). A History of Israel: From the Bronze Age through the Jewish Wars. B&H Publishing Group. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-4336-4317-0.

- ^ Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol.2, 1980, p.203

- ^ Lewis Spence, An Introduction to Mythology, Cosimo, Inc. 2004, ISBN 1-59605-056-X, p.247

References[edit]

- Shah, Idries (ed.), World Tales.

- Hollis, Susan T. (1984), Chronique d'Égypte, Vol. 59, pp. 248–57.

Further reading[edit]

- Ayali-Darshan, Noga (2017). "The Background of the Cedar Forest Tradition in the Egyptian Tale of the Two Brothers in the Light of West-Asian Literature". Ägypten und Levante [Egypt and the Levant]. 27: 183–94. doi:10.1553/AEundL27s183. JSTOR 26524900.

- Dundes, Alan (2002). "Projective Inversion in the Ancient Egyptian "Tale of Two Brothers"". The Journal of American Folklore. 115 (457/458): 378–94. doi:10.2307/4129186. JSTOR 4129186.

- Hollis, Susan Tower (2003). "Continuing Dialogue with Alan Dundes regarding the Ancient Egyptian "Tale of Two Brothers"". The Journal of American Folklore. 116 (460): 212–16. doi:10.2307/4137900. JSTOR 4137900.

- Hollis, Susan Tower. (2006). "Review: [Reviewed Work: Die Erzählung von den beiden Brüdern. Der Papyrus d'Orbiney und die Königsideologie der Ramessiden by Wolfgang Wettengel]". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 92: 290–93. doi:10.1177/030751330609200127. JSTOR 40345923. S2CID 220268932.

- Horálek, Karel. "The Balkan Variants of Anup and Bata: AT 315B". In: Dégh, Linda. Studies In East European Folk Narrative. American Folklore Society, 1978. pp. 231–261.

- Schneider, Thomas (2008). "INNOVATION IN LITERATURE ON BEHALF OF POLITICS: THE TALE OF THE TWO BROTHERS, UGARIT, AND 19Th DYNASTY HISTORY". Ägypten und Levante [Egypt and the Levant]. 18: 315–26. doi:10.1553/AEundL18s315. JSTOR 23788617.

- Spalinger, Anthony (2007). "Transformations in Egyptian Folktales. The Royal Influence". Revue d'Égyptologie (58): 137–156. doi:10.2143/RE.58.0.2028220. ISSN 0035-1849.

External links[edit]

- British Museum webpage on The Tale of Two Brothers

- Anpu and Bata, a Tale of Two Brothers

- The Tale of Two Brothers, a Fairy Tale of Ancient Egypt set in hieratic type by Charles E. Moldenke (Watchung, NJ: Elsinore Press, 1898)